Here is what the American soldiers who fought in the War with Mexico achieved by their victories:

- Upheld the right of an independent Republic of Texas to join the United States

- Established the Rio Grande as the southernmost boundary of Texas

- Added to the United States the territory that makes up the present-day states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and parts of Utah and Colorado.

Yet they have no national monument and to this very day, nearly 11,000 U.S. servicemen still lie buried in forgotten, neglected graves all over Mexico (as well as parts of the American Southwest). Only a few individual states and organizations have erected monuments or memorials to their memory.

One of the purposes of the Descendants of Mexican War Veterans is to try to correct this shameful oversight by erecting monuments and memorials honoring the "Heroes of '46." In this section of our website, you can learn what has already been done and just as importantly, what YOU can do to memorialize your own veteran ancestor.

Return to TOP

Last veteran, Owen Thomas Edgar, died 9/3/1929, age 98,

Last widow, Lena James Theobald, died 6/20/1963, age 89

Last dependent, Jesse G. Bivens, died 11/1/1962, age 94

[Source: Department of U.S. Veteran's Affairs]

Owen Thomas Edgar (1831 - 1929)

Owen Thomas Edgar, was, according to data from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the last surviving US veteran of Mexican-American War. He enlisted in the navy as a 2nd-class apprentice on February 10, 1846, and was discharged August 8, 1849. Edgar saw service on the frigates Potomac, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and Experience. After the war, he worked at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for 21 years, then worked at a bank for another 31 years. He spent his last ten years living at the John Dickson Home in Washington, D.C. Edgar died on September 3, 1929 at the age of 98 after suffering a fall from a chair that fractured his leg, and is buried in Washington's Congressional Cemetery.

Mexican War's Last Survivor, 98, is Dead

Washington, Sept 3 (AP) - Owen Thomas Edgar, only surviving veteran of the Mexican War, died Tuesday at the age of 98.

The distinction of being the last survivor of the Americans who had part in the war of 1846 came the day before his ninety-eighth birthday, June 17, with the death of William Fitzhugh Thornton Buckner, 101, at Paris, Mo.

Mr. Edgar was born at Philadelphia in 1831. In the war with Mexico he served on board the frigates Potomac and Allegheny. Prior to the war he had worked as a printer. He had been a resident of Washington for more than fifty years.

[source: Dallas Morning News, Sept 1929]

Return to TOP

Mexico City National Cemetery

Photo courtesy of American Battle Monuments Commission.

Throughout the War with Mexico it was the practice of the U.S. Army, following major military engagements, to bury the dead in mass graves on or near the battlefield where they fell. Generally, this task was performed as quickly as possible for one very practical reason: the warm climate in which most of the war was fought hastened decomposition.

The bodies of soldiers who died later of their wounds, or from some other cause, were also buried promptly, usually near whichever building was serving as an army hospital at the time. In towns garrisoned by American troops for long periods, burials often took place beside an existing campo santo (cemetery). Rarely were U.S. soldiers interred within the boundaries of a Mexican graveyard. The reason? Nearly all Mexicans were Roman Catholics, whereas most American soldiers were Protestants. Mixing members of the two faiths together in the same cemetery was frowned upon by both.

Only a few bodies were shipped back to the U.S. for permanent burial. Since the U.S. government did not assume this responsibility during the Mexican War, most of these were officers whose families could afford the expense. If the deceased was particularly well-known, other prominent citizens of the community from which he came might contribute to the cost of transporting his body. In such cases, it was also not uncommon for a small group of these same persons to travel to Mexico, to arrange for the disinterment and to accompany the deceased on the journey back to the states. On at least one occasion, one of these delegates became ill while in Mexico and himself died during the trip back home.

Apart from the few whose remains were brought home, the graves of most Americans who died in Mexico during the war were left unmarked and untended. To this very day, the bones of many an American soldier lie buried in some lonely, forgotten spot, in places known only to the men who have long since joined their comrades in death.

There is one notable exception to this otherwise sad commentary on the way our government has generally failed to bestow upon Mexican War soldiers the same honor and dignity granted to soldiers of later wars. On September 28, 1850 Congress passed an act approving "the purchase of a cemetery near the city of Mexico, and the interment therein of the remains of the American officers and soldiers who fell in battle or otherwise died in or near the city of Mexico." Consequently, on June 21, 1851 two acres of land adjacent to the English burying ground in Mexico City, was purchased from one Manuel Lopez for the sum of $3,000.

On July 21, 1852 Congress approved the appropriation of an additional $1,734.34 for "purchasing, walling, and ditching" the American cemetery in Mexico City.

By 1853, the bodies of some 750 U.S. soldiers were buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery. They were mostly the casualities of the battles that occurred in and near Mexico City in August and September 1847. Although a marker at the site suggests these men are "unknown soldiers," that is not the case. The names of all these men were recorded in casualty lists compiled at the time of the war.

Between 1851 and 1924, when it was closed to further burials, 813 civilians who died in Mexico City were also interred in the American cemetery, along with several members of the U.S. military. Some of the civilians were veterans of the Mexican War, the Civil War (both Union and Confederate), Indian campaigns, and the Spanish-American War. Others were members of the U.S. diplomatic corps, or their families. The first non-Mexican War burial was of a man named Reuben Willhite, who died on November 20, 1851. The last interment, it appears, was of a U.S. Army hospital steward, Charles Knowlton Sams, who died December 14, 1923.

On May 18, 1872, Congress appropriated $500 to reimburse the American consul for the cost of maintaining the "American Protestant Cemetery" for the past year and approved a salary of $1,105 for the cemetery keeper. A year later the American cemetery in Mexico City was declared a national cemetery, to be operated and maintained by the War Department. Finally, in 1947, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order transferring responsibility for the cemetery from the War Department to the American Battle Monuments Commission. Today, in addition to the Mexico City National Cemetery, the Commission maintains twenty-three other U.S. cemeteries around the world.

The remains of all the people buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery lay undisturbed and relatively forgotten until 1976 when a highway called the Circuito Interior was constructed. At that time, the cemetery was reduced in size to a single acre. The civilian remains were exhumed and re-interred in crypts constructed at the east and west walls of the grounds by the Mexican government. Simultaneously, the remains of the 750 Mexican War soldiers were re-interred in two new vaults placed in the center of the south end of the grounds.

A small monument made of white stone stands at the far end of the cemetery, above the vaults holding the remains of the men who died there during the War with Mexico. There is a brief inscription in gold letters on the monument's base. Presumably out of respect to the sensitivities of the Mexican people (or perhaps to prevent vandalism), it does not identify the men who are buried there as soldiers nor does it make it any reference to the war. It reads simply:

To the honored memory of 750 Americans known but to god whose bones collected by their country's order are here buried.

More than 800 other people, mostly Americans, are interred in crypts in the wall on the sides of the cemetery. In 1923, the Mexico City National Cemetery was closed to further burials.

Today, the cemetery is a tiny oasis of calm and quiet in the heart of Mexico City. It is located behind high walls at Virginia Fabregas 31, Colonia San Rafael - almost at the intersection of San Cosmé and Melchor Ocampo. The Plaza de la Constitucíon, or Zocalo, is about 2½ miles to the east and the U.S. Embassy is about 1 mile south. Memorial Day services, usually attended by the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, are held annually. It is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., except Christmas Day and New Year's Day. When the cemetery is open, a staff member is on duty to answer questions and escort visitors to grave sites.

Return to TOP

Monuments & Memorials in the U.S.

Kentucky's Mexican War Monument

|

Unlike other conflicts in which the United States has been involved, the war with Mexico has produced relatively few monuments or memorials. There is no national monument in Washington, D.C. Only a modest marble shaft, marking the mass grave of 750 U.S. soldiers buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery, has been erected by the federal government. The remaining few memorials have been erected by states (such as the Kentucky monument, left.), counties, or lineage societies.

|

Return to TOP

How to Obtain a Free V. A. Grave Marker

|

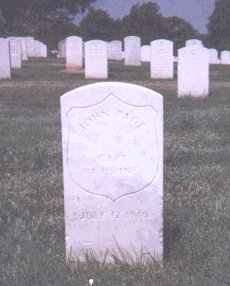

Below: A V.A. headstone marks the grave of Capt. John Page, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Palo Alto. Page's grave is at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery near St. Louis, Missouri. Photo by Steven Butler. Used with permission.

|

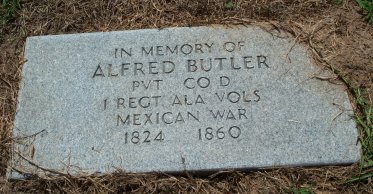

Unfortunately, most of the graves of U.S. soldiers who died in Mexico during the war are forgotten and unmarked. It is equally sad that the final resting place of veterans who survived the war and returned to the United States to live until their natural end are often unmarked as well.

Free veteran grave markers for the unmarked grave of any American veteran can be ordered from the U.S. Veterans Administration. They are available in a variety of types and are made from marble or bronze. Any person can order a marker. It is not necessary to be a descendant or relative.

To obtain an Application for Standard Government Headstone or Marker, write to the following address:

Monument Service

Department of Memorial Affairs

Veterans Administration

941 N. Capitol St., N.E.

Room 9320

Washington, D.C. 20420

Upon receipt of the application, complete it as directed and return it to the Veterans Administration. Be forewarned; your application may take as long as two years to be processed. Please also note that although the marker is free, you may have to pay to have it erected or placed in the cemetery. The stones are very heavy. The V.A. recommends that you have the marker sent direct to the cemetery.

|

Return to TOP

Graves Registry Project

In June 1997 the Board of Directors of The Descendants of Mexican War Veterans unanimously approved a project whereby the organization will compile a list of the known locations of graves of Mexican War veterans.

WE NEED YOUR HELP! In order to meet our objective, the DMWV is asking anyone who knows the location of the grave of a Mexican War Veteran to provide us with that information. To participate in this project, please complete a Graves Registration Form and mail it to:

DMWV National Office

P.O. Box 461941

Garland, TX 75046-1941

Thank you!

Note: In order to download, view or print the Graves Registry form, you will need the free Adobe Acrobat Reader. Click on the icon to download the reader if you don't have it already.

Return to TOP

|